Cinematic sociology is a remarkable way of understanding the theoretical subtleties of the subject being applied practically that eventually plug into a larger feedback loop, not unlike a serpent consuming its own tail. For example, the malaises of society prompt filmmakers to depict them in their craft and when audiences watch these films, they are forced to reckon with a mirror held up to their faces. This loop can either bring positive or negative change, but the evocation of some emotions in the viewer is guaranteed. The conclusion of the critically acclaimed filmmaker Deepa Mehta’s Elemental Trilogy, Water, released in 2007 after many privations, is one such film. Never before have audiences split so cleanly in the middle along the fractalized fault lines of religious, cinematic opinions, perspectives, and morality. Even today, the discourse Water garners is so polarized that viewers wonder why people huff about an otherwise one-dimensional depiction of gender relations in pre-independence India.

I aim to expand upon this duality that flows much like a meandering river in my cinematic review of Water from a multifaceted sociological lens. As a part of the submission for the practical component of the second semester of MJMC at the Faculty of Journalism and Communication, MSU Baroda, this is an extensive and comprehensive analysis which was meant to transcend the limitations of mere scholastic multitude and eventually get published. However, due to circumstances beyond my control, it never materialized. I do believe that this is one of the most detailed metaphorical analysis of one of Deepa Mehta’s Elements Trilogy Film series which would be appreciated in academia regardless of its peer-reviewed shortcomings.

The potential to apply the numerous theoretical concepts we’ve learned during the class is immense for this movie in particular from the selection. Due to its historic setting, a lot of the sociological issues that were rampant during the formative years of the country are at the forefront. It is very interesting to explore the layers of history that Water embodies. The 2000s were rife with fundamentalism and terrorism locked in a perverse dance and from that struggle, this beautiful art film has emerged. Thus, the emergent review attempts to capture the essence of these internal and external superstructures that bind and define the sociological complexities of Water and how it might still have reverberations that impact our modern society today.

Selection of Movie and Theme

After careful reflection on the available themes or conflicts that I could explore, I realized that the perspective of women, particularly gender relations, could be seen as an underlying keynote that invades almost every major issue such as caste, race, class, culture and even the techno-social sphere of the 21st century. Women have been commodified and objectified since the very inception of humanity. While one could argue about the bright spots in this dark abyss of oppression, they are too few and far between to build a reverse argument upon. Men’s rights have gained traction recently but only as a backlash to the rising demands of modern feminism. Although there is some merit to not subjugating the other side in the fervent demand for equality, one cannot simply erase the centuries of maltreatment women have had to endure under the hegemony of a society built by and for men. Therefore, Deepa Mehta’s Water immediately captured my attention as I turned to analyze the movies in the lineup. Though fundamental functionalists would vehemently disagree with the analysis of the current situation of women based on historical precedents, I do believe that there is profound emotional understanding and respect to be gained from such retrospective studies.

Interestingly, the themes depicted in Water find many deeper commonalities with the other movies in the selection. Dear Zindagi (2016) depicts a modern woman struggling with mental health issues such as anger and a fear of abandonment stemming from her past trauma. As she seeks professional help and support, the challenges and triumphs of her journey are evident in a society that still does not consider the mental and emotional needs of a woman as serious enough. Article 15 (2019) portrays brutal violence against the “lower caste” girls of a village in Uttar Pradesh. Oh My God (2012) offers a religious perspective but the hints of submissive femininity are rampant in the familial structures the movie inadvertently depicts. Badhai Do (2022) explores LGBTQ+ representation by shedding light on “lavender marriages”, where two homosexual people marry each other to avoid pressure from their respective families to settle down. The lesbian experience is represented beautifully in the movie all the while balancing it with the struggles men themselves sometimes have to face inside the rigid cage of patriarchy.

A common thread of gender relations flows through all of these movies and if one starts to follow this ball of yarn, it leads straight to the strongest portrayal of them all. Water (2007) not only precedes these movies in terms of release date but also in the visualization of the story’s setting. Therefore, selecting this haunting, fluid portrayal of the lives of widows in the dying embers of colonial India was a natural choice for me.

From a sociological standpoint, the feminist theory which is an offshoot of the critical social theory that major sociologists of the times such as Marx and Weber promoted, is a powerful contender for any human-centric study. The historical component of the movie lends well to the cause-and-effect analysis of the plight of widows in India before independence. The justifications offered by religion and the exploitation of the same by upper-caste men neatly tie religion, caste, and gender relations into this movie. Some of the more obscure themes of colonialism, corruption, representation of transgender people as deviant villains in pop culture, the power of a single ideology, and suicide also find a home in Water. I even spotted a Shakespearean parallel between star-crossed lovers in the Titanic (1997) and Water, although the male lead of the latter, Narayan (John Abraham), would ask me to compare this with Kalidasa’s Meghdoot instead. Therefore, Water is a holistic choice to analyze gender relations in Indian society.

Review of the Film

The symbolic motif of Water flows through its characters, story, narrative, and cinematography not unlike a river that weaves its way through steep valleys and lofty mountains, lush plains, and a sluggish estuary, finally meeting the edge of the sea. While to the novice, the impish and tempestuous eight-year-old Chuyia (Sarala Kariyawasam) may seem like the protagonist of the movie, I believe that the widows of the ashram are collectively the different facets of the same main character, portrayed at different stages of a singular lived-experience of being a widow in pre-independence India. Just like the tributaries of a mighty river.

From the start of little Chuyia’s stay at the ashram to the end of the eldest widow’s life, depicted by the sweet-starved Patiraji (Vidula Javalgekar) is thus, a single narrative. The various sides of the feminine (and by extension, the human) experience such as young love, stoic faith, glutinous greed, superstition, fear, and oppression are depicted by the different widows of the ashram. The only major stage in a woman’s life, marriage, is bereft from the characters’ lives; snatched by society and replaced by the starched-white shackles of widowhood. The movie begins with some lines from the Manusmriti and these become the subtones of the film:

“A widow should be long suffering until death, self-restraint and chaste. A virtuous wife who remains chaste when her husband has died goes to heaven. A woman who is unfaithful to her husband is reborn in the womb of a jackal.”

Pages would be insufficient to unpack the weight of these phrases but I would like to highlight two major points that are not immediately apparent: First, the author of the text, Manu, knows that by imposing chastity on a widow, he is condemning her to a life of suffering. Secondly, he does it anyway. Therefore, there is a clear motivation to make women suffer and there couldn’t have been a clearer indication of misogyny in Manu’s verses.

Although the movie was shot in Sri Lanka amidst rising tensions due to fundamentalist groups in India threatening to fatally harm Deepa Mehta and then actually destroying the set, the “Ganges” is another silent woman, flowing serenely with the other female characters of the movie, from the first shot to the last. One cannot watch the movie with all its splashes, dips, rainstorms, and splatters without imagining the chill of water on one’s skin. Or to those with poorer bladder control, a visit to the facilities. Even death in Water is phrased as “sacrificed to the river”, alluding to many cultures across humanity such as the Greeks and the Egyptians, viewing the afterlife as a journey across a river.

Many poignant dialogues highlight the entire experience of widowhood, from its confusing implications for a young girl to its damning inflictions on an older woman, which merit mention. Child bride Chuyia doesn’t even remember the fifty-year-old man she married whose death triggers the events of the movie. When informed that she’s now a widow by her penurious father, the innocent girl asks, “For how long?” The reason for the misfortune of widowhood falling on young girls is not a failing social system that marries older men to underage girls, but instead, it is the karmic retribution of the girl’s actions from a past life because, of course, she’s not old enough to cause genuine cosmic harm on her own yet. Not only is this thought process highly criminal, the answer to Chuyia’s question is even more distressing.

The sentence of widowhood for an eight-year-old girl is lifelong. The laws of religion are absolute in this castigation, snatching every semblance of identity, desire, and agency from women, forcing them into a life of renunciation. The woman is considered half-dead after her husband’s death because she’s half of him.

“How can a half-dead woman feel any pain?” asks Madhumati (Manorama), the obese matriarch of the ashram to the terrified and confused Chuyia upon arrival.

“She’s half alive too,” answers the little girl, after which this original thought is immediately silenced because widows are not afforded this luxury either.

The ashram is a dilapidated blue-grey with poverty climbing every wall like poison ivy and ruled by Madhumati. The other widows of the house acknowledge her authority despite her greedy transgressions out of fear. Some like Kalyani (Lisa Ray), the angelically beautiful young woman, are resources for Madhumati to exploit while others like Shakuntala (Seema Biswas), the erudite and pious older woman, only grudgingly allow Madhumati’s reign. The oldest widow of the ashram, Patiraji, is largely indifferent due to her weak health and meek voice. Chuyia, Kalyani, Shakuntala, Madhumati, and Patiraji can be considered as different stages of the same widow’s life and while their individual character arcs may seem hayward and not well-strung, together they form the core message of the movie which depicts women controlled and smushed under the bulwark of an unjust system.

The strands of these women’s stories can be viewed swiftly to understand the significance of each.

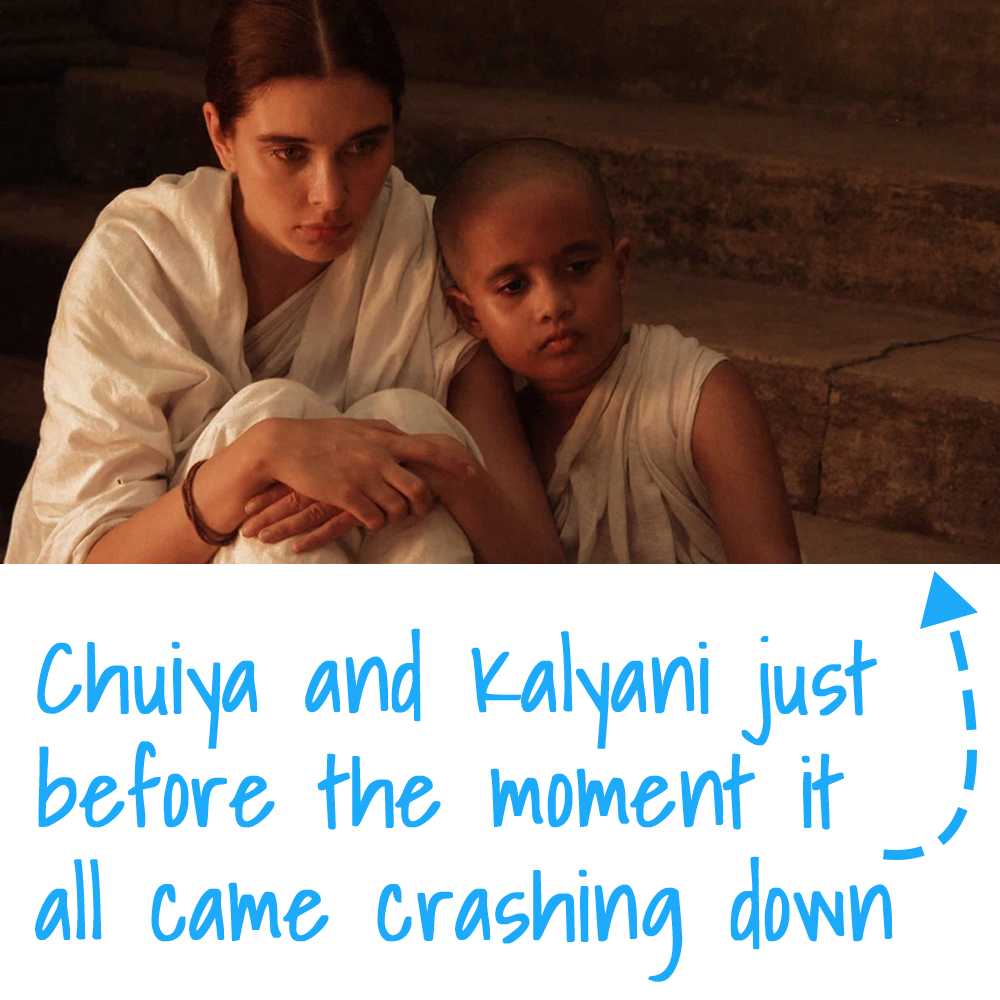

Kalyani is the only widow who is allowed to keep her hair long as she is being forced into prostitution by Madhumati for her wealthy Brahmin patrons across the river from the ashram. She befriends Chuyia because she was another child-widow (Kalyani had never even met the man whom she had married!) and together they progress much of the plot and interact with the other characters of the story. She falls in love with the young and handsome Narayan, an upper-caste bachelor swept up in the Gandhian ideology of social reform, justice, and nationalism. Her devotion to Krishna is rewarded in the form of this gentleman whom the movie doesn’t shy from depicting as a savior-hero, almost godlike man alongside another familiar male champion – Gandhi himself. This circular reasoning of the movie that promotes men saving women by standing up against the men who oppressed them is highly criticized in the contemporary discussions surrounding Water. Finally, when Kalyani chooses to defy tradition and start a new life with Narayan, she realizes that one of her clients had been Narayan’s father, and the helplessness of potential rejection by her lover or that of returning to a life of prostitution in the ashram under Madhumati isn’t something she can withstand any longer, and thus Kalyani drowns herself in the river.

Fascinatingly, while passive water drenches these women every moment of their waking lives, the only time the director depicts fire around them is when they are actively choosing their destiny. I’ll highlight this more in the subsequent thematic analysis of the movie. Chuyia is devastated by the loss of her friend and seeks revenge by strangling Madhumati’s pet parrot, the only time the guileless girl commits a brutal act. Although she regrets the murder immediately, the blows to her innocence are quick to follow when Madhumati, now lacking a resource for her old business, sends Chuyia across the river to be defiled. Thus, while the romantic arc between Narayan and Kalyani ends in abject tragedy, the heavy consequences are borne by Chuyia.

Shakuntala is the only widow in the ashram who can read and facilitates the exchange of letters between Narayan and Kalyani during the initial days of their romance. She follows a strict religious code, choosing to believe and have faith in the system that has put her in the ashram despite self-doubt. Seldom meddling in the lives of her fellow widows, she nevertheless has a sensitive and caring side which she tries and fails to hide as the events of the movie unfold. Shakuntala develops an attachment with Chuyia and is the first to care for her by applying a cooling turmeric paste on her recently shorn and itchy head. She’s also the only one who can stand against Madhumati’s tyranny and does so on numerous occasions to protect both Kalyani and Chuyia. She frees Kalyani from her room and asks her to marry Narayan but only once she realizes that while religion may not have left widows with many options besides sati, levirate, and renunciation, the law of the land does allow for widow remarriage. Thus, while the stoic widow may seem unaffected, Shakuntala is deeply entrenched in the welfare of her sisters and her own morality. This commitment can be summarized through the following dialogue between Shakuntala and the priest Sadananda (Kulbhushan Kharbanda).

“How close are you to self-liberation (moksha)?” asks Sadananda.

Shakuntala says, “If moksha means detachment from worldly desires, then I’m far from it.”

Madhumati, along with the transgender woman Gulabi, are the antagonists of the movie, besides the suffocating and perverse social system at the time, of course. She represents the idea that while the patriarchy may be subjugating women, some women are no better and would profit from this because women are ultimately humans too, and suffer from the same predilections. Madhumati is greedy, angry, and offensive. Steeped in drug abuse and indulgence financed by Kalyani’s prostitution, she takes a lion’s share of the meager income the ashram earns through begging and promotes her addictions over the basic needs of the other widows. Her greed is so immense that she doesn’t even allow some spare money for Patiraji’s funeral. Madhumati forces Chuyia into prostitution after Kalyani dies and for that she reserves a special place in the audience’s disdain, despite the movie trying to show her vulnerable side. Gulabi is a character that was overlooked at the time for “being a natural villain”. But recent awareness surrounding trans representation has allowed for new light to shine on her portrayal. While her actions are inexcusable, the conditions for trans women were no better in Indian society than for widows at the time. Gulabi could also be seen as yet another trans character vilified in pop culture, normalizing the idea that all trans people are deviants and evil.

Lastly, Patiraji is the oldest widow of the ashram who connects with Chuyia because of her love for sweets. The oldest and youngest widow both remember the feast and the clothes from their respective weddings, but not much else from their marriages. This is a poignant indication that if a person’s innocence is taken away before it is meant to, the trauma carried by them can seemingly cause time itself to freeze. Before her death, Chuyia spends what little coin she has gathered to give a single laddu to her “bua” (Patiraji, as she’s referred to in the ashram). This scene is one of the most heartwarming in the movie as it depicts Chuyia rejecting the expectations of society and doing something small for another person that could bring her joy. The cinematographic heft of her funeral is felt by the audience as the widows do not light her pyre, but let her float adrift the river, guided by raised lamps above the body. This is another scene where the active agency of fire is denied to a widow and water is all she has, in this case, because Patiraji did not choose to die. This is different from Kalyani’s funeral where fire is actively shown in the shot, indicating that she chose her own death.

Tearing this narrative away from the widows is the wave of change and nationalism that is sweeping the country and the movie. Seeing no other escape after Chuyia is sexually abused in the final act of the movie, Shakuntala deposits the young girl into Gandhi’s ideology of truth. In the last scene, the pair flows with the metaphoric “river of people” down to the platform where Gandhi is giving a speech. After hearing his iconic “God is not Truth, Truth is God” message, Shakuntala decides to save Chuyia by putting her on the train with Gandhi. Luckily, Narayan is also on board the same locomotive, leaving the colonial, fatigued, destructive, and oppressive system of his home for the utopia that a free country could provide. He takes Chuyia with him.

The symbolic train of modernity finally proves to be the escape from the helpless river of tradition that would’ve awaited Chuyia back at the ashram, and Water concludes its haunting story of grief, loss, and ultimately, triumph.

Deepa Mehta has captured the visceral world of widows in pre-independence India all the while presenting it with an ethereal azure symbolism that demands that the viewer desire to reach into the screen and change the oppressive beauty that stalks the characters in every scene. The cinematography is well-deserving of its “Best Foreign Film” Oscar nomination in the subsequent year. The actors have done a phenomenal job with the spotlight being stolen completely by Sarala Kariyawasam (Chuyia). While the story structure could’ve benefited from a tighter focus on the impact Chuyia has on the other characters, I believe that if one were to observe the movie from my initial perspective of it being a collective story of the widows rather than a focused experience of the youngest widow, the reasons for Mehta’s approach become self-evident.

In essence, Water is a snapshot of a time in history with all its shades of blue; a window into a world that has passed us by but its echoes still influence us today.

Perspective

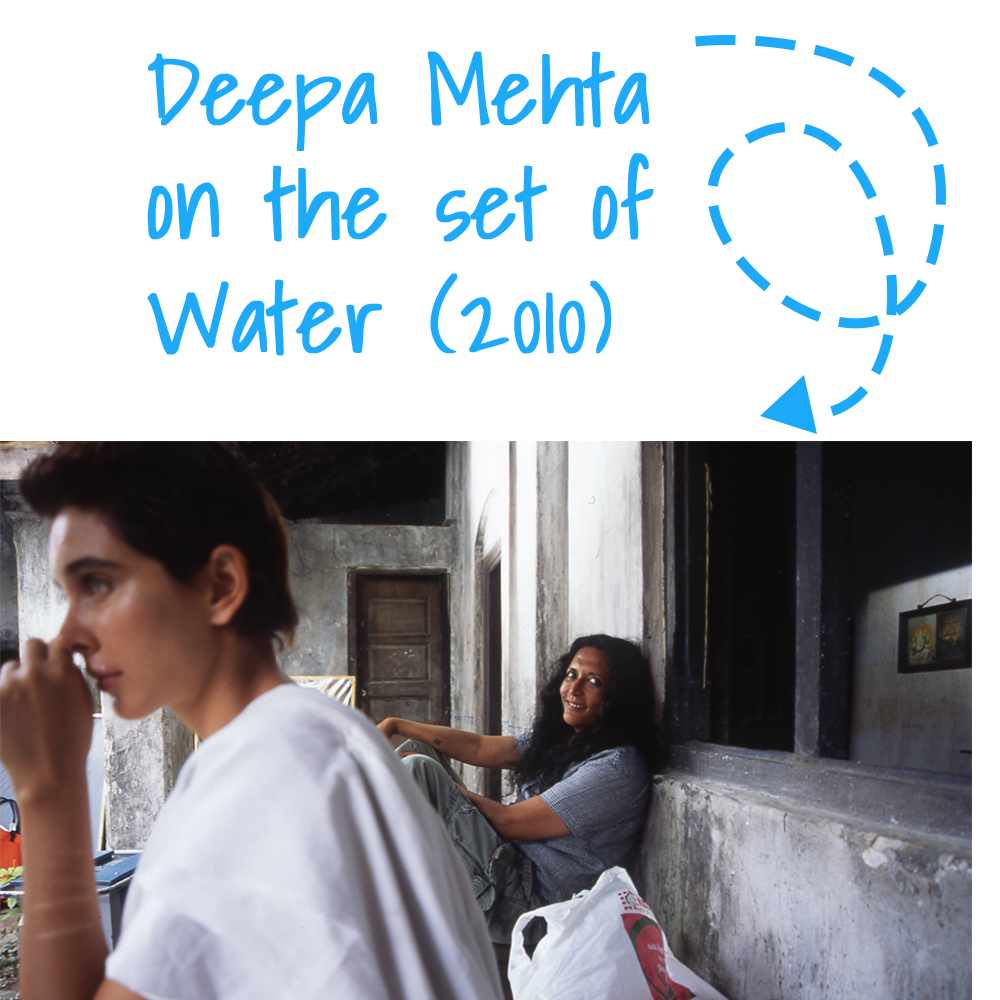

Released in 2007, Water is the conclusion of powerfully expressive and fearlessly creative, Indo-Canadian director, Deepa Mehta’s Elemental Trilogy which captures the female experience in different eras, contexts, and themes. Fire (1996) sparked controversy upon its release as it depicted homosexuality and the perils of arranged marriage in the (then) concurrent confines of Indian patriarchy. Earth (1998) showed how religious strife had torn apart men and women during the partition of India. Water, with its themes of sociocultural mistreatment of widows, the absolutism of religion, and misogyny had such a delayed release because of the reluctance Indian society had at the time for Mehta’s work, especially the more radicalized sections of Indian society such as the Shiv Sena, the BJP and the RSS. Death threats were sent to Mehta by these factions and hooligans also destroyed the set of the movie, prompting the director to use pseudonyms for the movie and relocate it to Sri Lanka for the shoot. The rise of Hindu fundamentalism in response to Islamic fanatism and terrorism (the 9/11 attacks in the US and the 2001 attack on the Indian Parliament, for example), left not just India but the whole world fraught with dread. This acted like the stage upon which the challenges to Water were posed.

The media, audiences, as well as the many famous actors and composers who had contributed to Mehta’s work, were also divided in their opinions about the movie. Critics questioned the validity of the “man-savior” and the colonial lens through which an “exotic” India was being depicted. But no one can deny the emotional intensity of the movie and how the largely middle-class audience responded to the story on a spiritual level. The slow rise of middle-income houses and the emergence of a new social class at the time also prompted an interest in movies with a message rather than just viewing cinema as a form of entertainment by the masses. More and more women began joining the workforce as the IT boom began in the country, allowing movies such as Water to be even more impactful. However, while the movie may have been an educational insight into a historical reality, Indian society is still not ready to accept it fully. This is proved by the fact that the movie is still not available on any OTT platforms in the country today.

The actual historical perspective of the movie has been alluded to in my review with its pre-colonial setting, the rise of nationalism, and Gandhian philosophy in the subcontinent. Women bore the brunt of the oppression in Indian society with the condition of the widows being inhuman with no strict, secular law protecting them. The Non-cooperation movement and the emphasis on self-rule and self-production was strong after Gandhi captured the nation’s imagination because of his philosophy of non-violence and peaceful resistance.

Ironically, Mehta’s most controversial film also became her most critically and commercially successful one yet. This defines the historical, cultural, and societal context upon the release of the movie in the late 2000s.

Comparative Analysis

The representation of widowhood in Indian cinema and largely pop culture has been struck by a melancholic strain that is hard to ignore. Gender relations somehow falter even more in the absence of a man than in his presence. While some movies show stark realities like Water, others choose to romanticize widowhood instead, bringing some sort of wish fulfillment to the whole concept. This harrowing experience in any woman’s life is largely used as a plot device and rarely have depictions of gender relations come close to identifying the true ramifications and societal reactions to this aspect of sociological study.

I’ve elected to analyze a broader cross-section of gender representation vis-à-vis widowhood much like the movie Water does with its characters rather than do a qualitative, deep dive into the comparison of one or two movies to capture the evaluation of the representation of widowhood and its sociological consequences in Indian society.

One of Deepa Mehta’s own films offers a look into a failing middle-class marriage in the movie Fire (1996). While divorce is not an option, the chains of the patriarchy are seemingly broken by lesbianism. One of the protagonist’s husbands takes a vow of celibacy, effectively rendering his wife a living widow. Adultery is often a common theme of such representation in pop culture but none was as scandalous as the relationship shown between two married women finding solace in each other’s embrace. The hints of female liberation that lie away from masculinity remain a recurring theme in the following movies as well.

Kaksparsh (2012) (translated as “A crow’s touch”) remains a powerful piece of Marathi cinema that has been widely appreciated by audiences. It explores the concept of levirate but in a consensual setting instead of the forceful adoption that is usually portrayed. The chastity of a widow is a central focus of the movie. It draws many parallels with Water as both are historical movies set in a time when widows had very little agency or rights. Upon the death of his brother, the male protagonist of the movie vows that his bride will not be touched by any other man but ultimately falls in love with her himself. While the attraction is mutual, the end of the movie is tragic. Instead of remarriage, the widow in question dies to keep her lover’s vow, adding yet another tragic ending to the plethora of depressing depictions of widowhood in popular imagination.

Chokher Bali (2003), based on Rabindranath Tagore’s famous book of the same name, depicts the life of a widow who falls in love with a married man during the Bengali Renaissance in the early 1900s. It romanticizes widowhood in the light of the social reform movement gripping Bengal at the time with the female lead playing the role of a temptress having control over the two male protagonists’ desires. Even this modern approach fails to portray a happy ending for the widow as she leaves both men with a letter and disappears.

Ek Chadar Maili Si (1986) is based on Rajinder Singh Bedi’s classic Urdu novella by the same name set in undivided Punjab. In stark contrast to Kaksparsh, this movie depicts a violent portrayal of levirate where the poor widow is subjected to the same torture her late husband did by his younger brother. And it is made even more traumatizing when the almost mother-son-esque relationship between the widow and her brother-in-law is factored in. The thought that the community (or society) can so easily and arbitrarily govern an individual’s sexuality and personal life is the frightening realization that this movie brings. Ek Chadar Maili Si ends with the widow leaving her husband’s brother and returning to her maternal village. Thus, it is the only movie where the widow has not died, disappeared, or become a widow but rather accepted a life of solitude and a social recluse – a more palpable fate to most.

Lastly, I would like to explore a more recent portrayal of widowhood that brings with it the nuances and clever sensitivities of the digital age. Pagglait (2021) is a Hindi-language black comedy that follows a young widow as she navigates dealing with the loss of a husband quite early in the marriage, family expectations, and societal obligations. Coming close to levirate again, Pagglait does something that is distinguishably different from its predecessors on the same subject – it gives the woman the freedom to make her own choice. The widow while promising to take care of her in-laws, returns to her professional career and comes into her own as a woman in this inspiring tale of self-reliance and courage. While others around her expect to grieve a certain way, she learns to accept her self-expression and emotions as valid and deserving of their own space in society.

However, while portrayals like Pagglait must be celebrated for their authenticity and bravery, it is important to remember that the other movies were set in a time in history when women found it impossible to escape the iron cage of patriarchy strangling their very right to exist at every turn. It is due to the stories that came before to educate and inform the masses that large-scale social change has become possible in India.

Viewer Reaction

Any sociological evaluation is incomplete without analyzing how the masses perceived the content and if it brought about any significant change in society’s preconceptions on the issue. There were three major perceptions and reactions to the movie Water released in 2007 – the extremist view, the critical interpretation, and the opinion of the masses.

The extremists were quick to denounce the movie on religious grounds and questioned the motives of each person involved in making the film. Their actions were quick and violent, with an intent to fully repress any expression of the movie’s content in the country. While they had little power over the international release of the movie, I do believe that it is their continued influence in today’s polarized India that prevents the streaming of Water on OTT platforms in the country. The widow ashrams depicted in the movie still exist in Varanasi today, so to show this film to contemporary audiences is of the utmost significance. The filmmaker was accused of being anti-Indian and against the traditional values of the country. After the analysis of the movie, it seems that most of these views were largely an exaggerated attempt to silence an Indian woman from making a film on a sensitive issue. Even the most extreme radicals in the country now do not attempt to explain away the evils of child marriage, sati, female infanticide, and the discrimination against widows, and I would like to believe that this is partly because of daring movies like Water.

The movie received widespread critical acclaim though its narrative was disparaged for being unfocused and a little wishy-washy in the middle. Andrew Pulver of The Guardian states in 2007 –

“But whatever sensitivities Mehta’s film may have roughed up on the subcontinent, there’s no doubt that in a more neutral arena, over here, Water emerges as a civilized, empathetic and humane treatment of its subject.”

This view is also supplemented by the famed movie critic, Roger Ebert, accenting some of the cinematic depictions in the movie surrounding poverty and the realness of being Indian.

“The film is lovely in the way Satyajit Ray’s films are lovely. It sees poverty and deprivation as a condition of life, not an exception to it, and finds beauty in the souls of its characters. Their misfortune does not make them unattractive.”

Many research papers have now been published on the movie, analyzing its relationship with caste, depiction of violence against women, and of society as portrayed in the movie. Dissertations, review articles, and journal archives have substantial analytical work available as well for scholarly views on Water. The common ground these find is that while the characters may not be the strongest, the visuals and the soul of the movie outshine its lacunae, providing a powerful glimpse into a hitherto unseen world on the big screen. Many also claim that Mehta’s courage in finishing the movie has inspired female directors not only in India but internationally as well.

Finally, the critical discourse on informal reviewing websites such as IMDb and Reddit has users debating the authenticity of the movie and its portrayal of widows. Many do not focus too much on the complexities of the characters but on the actors’ one-dimensional theatrical prowess, claiming that the performance is “fake”, “cliché”, or “too simple”. “Tragic theme undermined by clichés” and “The statistics stated in Water and the message of this movie is questionable!” echo the soul of the many arguments made against the movie. While some of these reviews are from as latest as 2023, many are from around the time the movie was released.

When I asked my father about the reception of the movie, he said, “The audience liked the cinematography far more than the acting or the story. The little girl’s story was heartbreaking and moved many in the theatres to tears wherever it was screened.”

Overall, as much as I would like to believe that the movie created a lasting impact on Indian audiences, evidence would point to the fact that it caused mere ripples of discomfort that were soon forgotten. People acknowledged that women need to be treated better in society but failed to provide any concrete steps towards achieving this ideal. Historical movies tend to make audiences believe that these bone-chilling problems end with the movie itself. However, time has been kind to Water and I hope that through sustained conversation and awareness, issues like widow remarriage won’t be relegated to footnotes in the pages of history. Instead, they shall remain as cautionary tales to future Indians to not let their citizens face such abhorrent adversity.

Theoretical Structure

One of the most prominent sociological theories that even the characters use to justify the condition of widows in pre-independence society is functionalism. Radcliffe-Brown’s concept shines bright when Narayan explains that widows are subjected to living in ashrams away from society because the cost of bearing another human to feed in those impoverished times was too great.

“Disguised as religion, this is just a business,” he says bitterly.

As Radcliffe-Brown emphasizes society above the individual’s needs, it encapsulates how families are willing to discard their daughters who are uneducated, physically weak, and won’t help the household run in any way except by being a “burden”. However, I disagree with functionalists on the importance of studying history to find out reasons as to why socio-cultural structures exist and there isn’t a stronger example than Water.

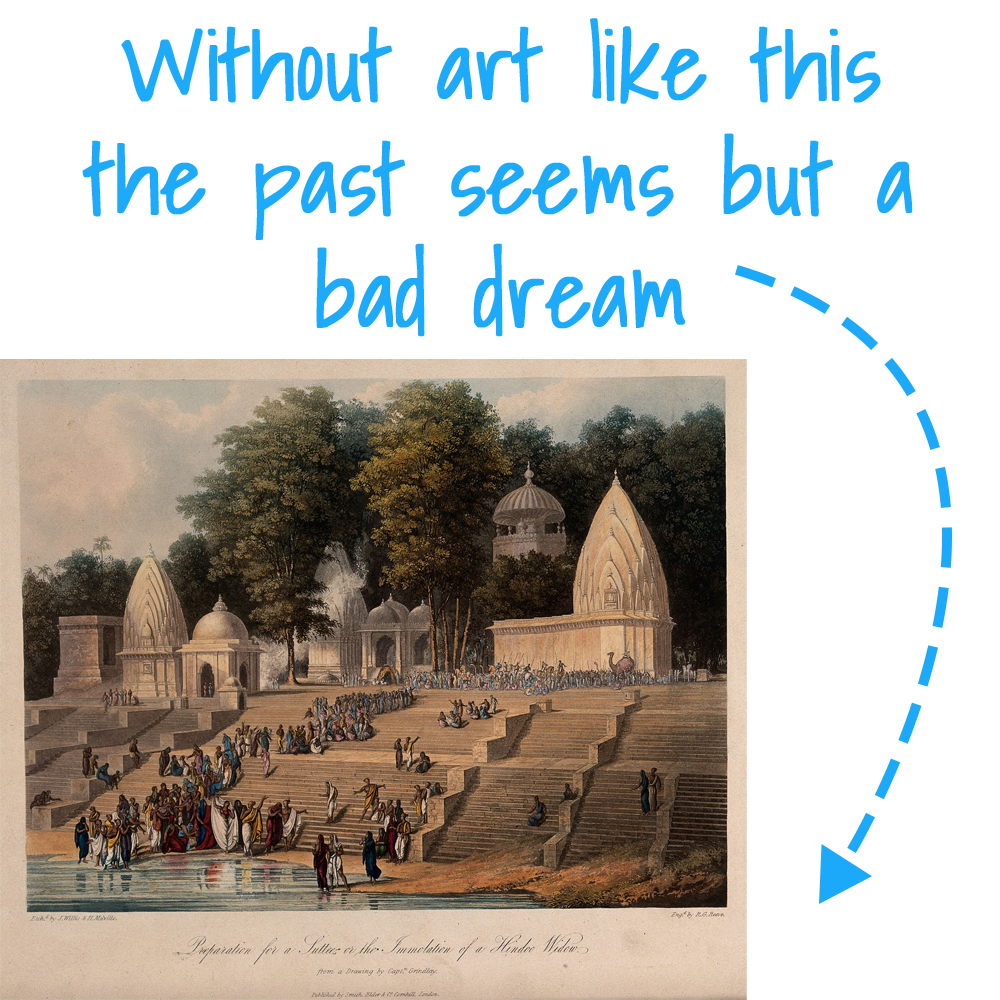

Scriptures, religion, and history are intertwined in Indian society and often people will follow something even if it has no practical purpose just because tradition demands it. For example, Sati was a barbaric practice but just to prove the godly standard of marital devotion, women were sacrificed. Therefore, in complex societies like India, it is pertinent to study both the practical (or functional) reasons why social structures exist as well as historical and cultural precedents.

Fundamentals of conflict theory are rife in the exploitation of widows by the upper caste Brahmin men who create rules to classify them as untouchables but under the cover of the night abuse them as prostitutes. The reasoning given by Narayan’s father is even more sickening and dangerously close to what religious leaders in other religions such as Islam and Christianity have also stated – “It is a boon to sleep with a man of god.” This is used as justification to rape subjugated and oppressed women and children. This becomes a situation ripe for revolt according to Marx when the depressed classes realize that their oppression stems from a single source – the elite. In Water, Shakuntala realizes that widow remarriage is permitted by law through the priest (spokesperson) Sadananda.

Her immediate question is, “Why haven’t we been told about this?”

The response is chilling. “People only care about the laws that suit them.”

At least this interaction allows Shakuntala to gather the courage and free Kalyani from Madhumati’s imprisonment, which is exactly the model of conflict resolution that Marx has proposed. Gandhian ideology also seeps into every facet of the movie much like the proverbial water it is based on. The power of a charismatic political leader is thus shown. It is strong enough that Shakuntala is even willing to submit Chuyia to strangers on an outbound train rather than let her stay in the ashram.

Symbolic interactionism is also rampant in the caste structures and the parallels between untouchability and the ritual purity and pollution practiced against widows. The thematic analysis of certain dialogues that are peppered in the movie highlights this expertly:

“You’ve polluted me with your touch and now I’ll have to bathe again,” says an upper caste woman to Kalyani at the ghats.

“If we eat with Kalyani, the promiscuous widow, how will we digest our food?” asks another widow to Madhumati in the courtyard of the ashram. “It’ll become polluted.”

“Don’t let your shadow fall on the newly-wed bride,” warns a priest to Shakuntala as she passes by to drink water from a well near the river.

“Widows don’t eat fried food,” comments the sweet vendor to Chuyia at the market outside the temple of Krishna.

“If widows remarry, we’ll all be sinning, not just you,” says Madhumati to Kalyani when she expresses her desire to marry Narayan.

When Chuyia naively asks, “Where is the house of the man-widows?” the reaction by her fellows is immediate. They condemn her to death by having her tongue ripped out and pray to protect men from such a horrid fate. This demonstrates how the system has brainwashed women to continue their own oppression.

These are some of the interactions that a caste-subjugated populace promotes to not just those crushed under the weight of the varna system but anyone society thinks of as impure and in this movie that group is widowed women. These symbols have been used by society to create a strict hierarchy of dominance that even those who are oppressed refuse to break because of the impact these symbolic interactions have on their lives.

Surprisingly, these caste barriers are simultaneously broken and upheld in the widow ashram. Madhumati praises Patiraji’s luck for having a Brahmin widow beside her deathbed but at the same time, the widows don’t follow caste considerations in their own house. The widows are equal in the demerits of their suffering but only find distinction in the few advantages offered.

Lastly, the theories of colonial oppression, misogyny, and suicide are also depicted in the movie, especially in the scenes Narayan shares with his anglicized friend who prefers Shakespeare to Kalidasa, whiskey to toddy, and the English government to self-ruling Indians.

Summary

Water is a beautiful film that not only unapologetically depicts history but also educates the audience. The motif of water trickles down to every aspect of the character’s existence whether it is when they are dancing and rejoicing for the arrival of the rains or when their depleted bodies are being carried into the afterlife by the river. The former is one of the most memorable moments of the movie when Kalyani and Chuyia, after their brief meeting with Narayan, are dancing as the music swells into a thunderstorm of melody. The only time characters are depicted interacting with fire is when they are making their own choices like when Kalyani takes a torch to light her path toward Narayan and finally when she’s burned at the pyre after her suicide. Chuyia’s fiery rage is calmed by splashing water onto her or when no one is around to do that, by her own tears of remorse.

When told that social reforms shall eradicate all traditions, Kalyani hesitates and says not all of them should be eliminated. She’s thinking about her devotion to Krishna and I agree with her. The festival of Holi celebrated by the widows is the singular day colors except white are allowed in the ashram and this could only be possible because of the liberal aspects of an otherwise rigid religion. These features and a profound understanding of the power of religion over society are what make Water an immensely impactful movie.

The sociological elements of the movie are strong and many theories of import such as functionalism, symbolic interactionalism, and conflict theory can be identified in it. The reactions of the audience and the public betray a certain narrative that had gripped the nation at the time which still finds similarities today.

While the movie faced a lot of criticism at the time of its release, I believe that with time, there is a sense of maturity and grace that has been bestowed upon it now. I would like to conclude my analysis of Water with a quote from Kalyani that summarizes this attitude perfectly, “Everyone can live like a lotus, untouched by the dirt, rising above it to provide beauty to the world.”

Resources

- The Guardian’s review – Andrew Pulver, 2007.

- Roger Erbert’s blog, 2006.

- Movie Review : Water (A Reflection of Society of 1938).

- Problems of Exclusion: Widowhood in Deepa Mehta’s Water.

- Gender and Caste Violence in Deepa Mehta’s “Water”

- Verma, P. (2005). Born to Serve: The State of Old Women and Widows in India. Off Our Backs.

- Rajan, Rajeswari Sunder, and You-Me Park. Postcolonial Feminism/Postcolonialism and Feminism: A Companion to Postcolonial Studies, Edited by Schwarz, Henry, and Sangeeta Ray, Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 2005.

- Deepa Mehta impresses with Water, 2007.

- Saltzman, Devyani. Shooting Water: A Memoir of Second Chances, Family, and Filmmaking. Newmarket Press, 2006.